Evangelicalism, as a movement, took shape during the Great Awakenings of the 18th and 19th centuries. It emphasized personal conversion, the authority of Scripture, and an urgent call to spread the gospel. By the 19th century, new theological ideas, such as the doctrine of the Rapture, emerged, gaining traction among certain Christian groups, particularly in the United States.

The Rapture—the belief that Jesus will return to take true believers to heaven before a period of tribulation—was not widely accepted in the early church. It was popularized in the 19th century through the teachings of John Nelson Darby and later reinforced by the Scofield Reference Bible. This doctrine aligned with the anxieties of a rapidly changing world. Industrialization, war, and social upheaval left people searching for certainty. The Rapture provided a simple but fear-driven framework: believe the right way, or risk being left behind.

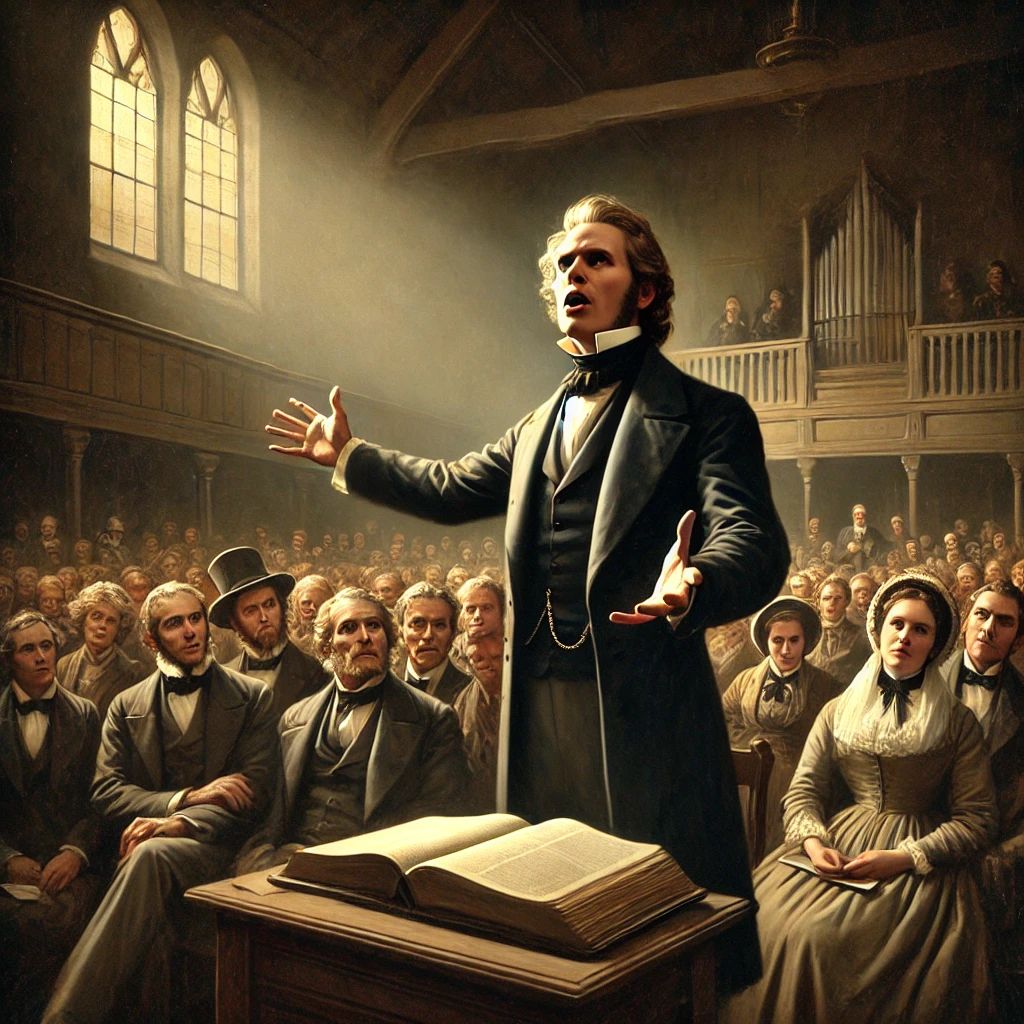

But fear was never the foundation of the gospel. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, did not preach the Rapture. His focus was on holiness, grace, and the transformation of the heart. Wesley emphasized salvation as a lifelong journey of sanctification, where God’s grace works before, during, and after conversion. His sermons centered on love, holiness, and social justice—not on trying to scare people into faith. To Wesley, the gospel was not about escaping a doomed world but about becoming more like Christ and working for the kingdom of God here and now.

I do not believe in the doctrine of the Rapture because it distorts the heart of the gospel. Rather than emphasizing God’s love, it often becomes a tool for fear-based manipulation. Many evangelical churches use the threat of being “left behind” to pressure people into conversion. Instead of drawing people toward the message of Jesus, it pushes them into belief through anxiety over eternal damnation. This is not the gospel. The gospel is good news—that God’s love is for all people.

This became deeply personal for me when I was serving as a United Methodist minister. My 13-year-old daughter was attending an Evangelical church with her friends, where the focus on hell was relentless. One day, she asked me, “Daddy, why don’t you preach about hell?”

I told her, “Because I don’t think I should give evil a place in the church. I try not to preach people out of hell but into heaven.”

That has always been my belief. Jesus came into the world to preach the good news: that God loves all people. That all people are children of God. That God’s love is stronger than fear, stronger than punishment, and stronger than any human-made doctrine.

John Wesley understood this. He preached that God’s grace calls us into a deeper relationship, not through threats of destruction but through love that transforms. The gospel is not about who gets left behind—it’s about who gets embraced. And in God’s love, no one is abandoned.